FORT MYERS BEACH, Florida – Houston is no stranger to the devastating impacts of hurricanes. Just mention the names of Ike and Harvey in the Houston area and you’re likely to hear someone’s personal story of tragic loss.

If you ask those same people the differences between the two storms, there’s a good chance they’ll talk about the historic rain from Harvey and the storm surge from Ike. However, they were two dramatically different hurricanes.

MORE: KPRC 2′s 2024 Hurricane & Flood Survival Guide

Every tropical system is different; in size, and impact, and they can result in different damages if they were to hit certain regions of the country.

The most recent major hurricane to hit a metro area was Hurricane Ian, which leveled much of Southwest Florida in September 2022. Ian brought storm surge levels of 15+ feet with Category 5 winds to the small barrier islands of Fort Myers Beach, Sanibel, and Captiva.

EXPLAINER: Hurricane categories: What do they mean, exactly?

Hurricane Ian was a dramatically different storm than Hurricane Harvey, which flooded much of southeast Texas after the monster storm stalled and sat overtop of our region, dumping rain like Houston’s never seen before.

It’s why KPRC2′s Gage Goulding paid a visit to where Hurricane Ian made landfall.

Along those sandy beaches are lessons that we can learn here in Houston to help us better weather a storm.

It’s on Fort Myers Beach where we also learned a storm just like Ian could have equally devastating impacts right here at home.

Hurricane Ian vs. Hurricane Harvey

To understand the differences between Hurricane Ian and Hurricane Harvey, we traveled to Florida Gulf Coast University in Florida, where researchers are studying hurricanes of the present and past.

“Harvey was, I think, a slightly weaker storm. But they obviously had two very different, kind of, the effects,” said Dr. Joanne Muller of Florida Gulf Coast University.

During Hurricane Harvey, much of the region was spared the worst of storm surges and even winds. However, what we didn’t get in those departments fell from the sky in the rain. Many parts of the Houston metro area received several feet of rain.

Meanwhile, Hurricane Ian brought a wall of water towering more than 15 feet deep in some places. This storm surge combined with Category 5 winds leveled many buildings on the barrier islands and pushed storm surge miles inland.

Again, being out in the elements, especially on a beach pier, is a DANGEROUS and LIFE-THREATENING idea.

— Gage Goulding - KPRC 2 (@GageGoulding) September 28, 2022

Do not risk your life in this storm. #HurricaneIan @NBC2 pic.twitter.com/cY5mlnJraE

That same wall of water could’ve hit the beaches of Galveston if a storm like Ian were to eye up the Texas Gulf Coast.

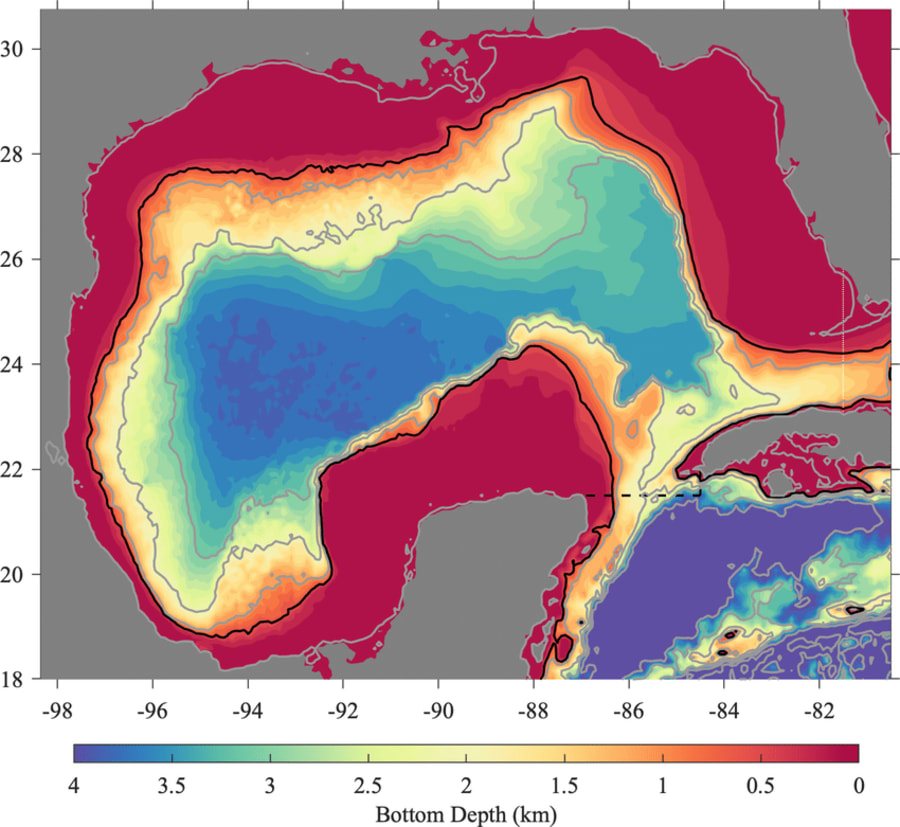

“We have this kind of wide platform that exists all along the Gulf Coast,” said Dr. Muller. “And it means that we are much more likely to see storm surge in the Gulf as opposed to, for example, the east coast of Florida. So, you could run the same hurricane model to make landfall for the same sort of storm in Miami and in your area of, let’s say Houston or Galveston, Texas, and you’ll see a much greater storm surge in the Gulf than you would see on the east coast of Florida because they don’t have that same platform. It’s kind of almost like you’re in a pool and you’re stepping up to steps to get out of the pool. So that exacerbates the storm surge.”

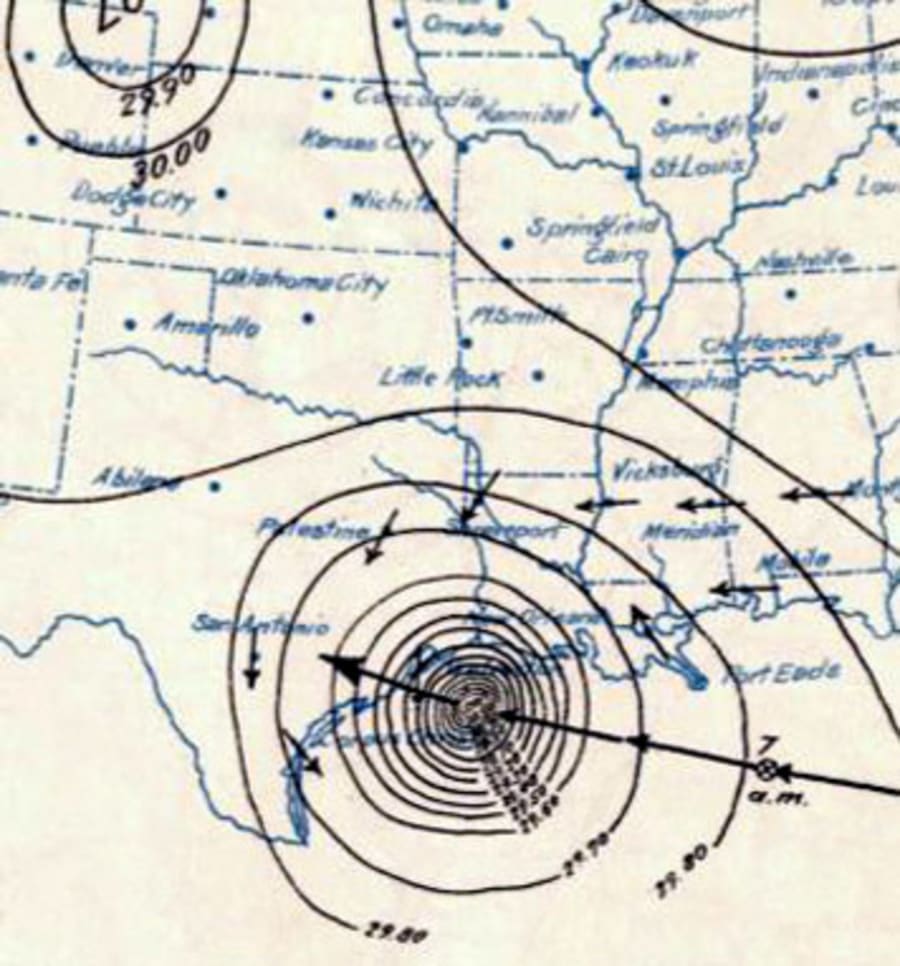

We’ve seen that exact scenario play out before in Houston with storms like Hurricane Ike and other past storms, some before modern technology.

“I was just looking at numbers this morning from the Galveston storms. And we found some historic records of 20 feet for the I think it was the 1900 Galveston storm, storm tide, number of 20 feet,” Muller said.

“Unfortunately, all of these old storms, you know, we didn’t have tide gauges back then in all these areas like we do today and all these sophisticated buoys,” Muller said. “But we do have these historic reports. And then you had the 1950 or 15 storm. And we have a number of 15 feet. Hurricane Ian was kind of sort of 11 through I think they they did find some high water marks of 14 to 15ft. These are really significant storms.”

Why is all of this information important?

Dr. Muller and her team use this information to understand the impacts of historic storms and equate them to today.

In simple terms - what was the storm like back then and what would it look like if it hit the same area right now?

“You can take that damage number and you can adjust it for inflation, for changes in wealth, U.S. wealth, and then also for metrics like either population or housing units,” she said. “We like to use housing units and then we multiply that all out to figure out to essentially normalize that initial damage estimate from 1915. And that storm is greater than $100 billion. That 1915 storm, for example.”

Using Modern Technology

Fast forward more than a century and the technology researchers have at their disposal is changing the way they can look at hurricanes.

Michael Savarese from The Water School at Florida Gulf Coast University employs the assistance of a drone that has a price tag of roughly $100,000.

Gage Goulding: “What’s the point in all this money flying through the sky, looking at the beach?”

Mike Savarese: “Well, our work here is sort of helping communities determine how Ian impacted, the coast and then learn from those impacts.”

The drone is outfitted with a LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) sensor on the bottom.

Using this drone, they can scan the beach. His team did this before Hurricane Ian hit, immediately after, and the years following.

“The mapping we’re doing sort of reveals vulnerabilities along the coast. And if you know your vulnerabilities, you can protect, against them,” Savarese said.

Those vulnerabilities include areas of the beach that were badly eroded by storm surge, which can undermine buildings leading to even more destruction.

Gage Goulding: “What were the biggest findings that opened your eyes?”

Mike Savarese: “We realized that the storm surge actually causes problems twice, once coming in the so-called flood surge and once going out the ebb surge. And that returning water created, oh, horrendous conditions, in fact, most of the damage.”

The worst of the erosion is near beach access points, which can sometimes be purposeful cuts in dunes or seawalls, which are meant to protect us from storm surge.

“There’s no reason why beach crossovers can’t be constructed. A lot of areas have boardwalks that go up and over dunes,” Savarese said.

In Tune With Mother Nature

While some researchers are using technology, others are tapping into the wisdom Mother Nature has to offer.

One of those researchers at Florida Gulf Coast University is Win Everham.

“Nature does more in resilience than it does in resistance. It does more in recovery than it does in prevention,” Everham said.

He’s studying how nature handles hurricanes in hopes of finding translations to human nature.

“One of the answers is that different species handle it in different ways,” he said. “Every mangrove that exists on this landscape has seen hurricanes through evolutionary time. Some of them manage it by having babies in place for when the hurricane hits. Some of it manages it by re-sprouting and recovering a lot of them. And you can see right back there, see how many mangroves are flowering right now.”

One of the best translations from the ecosystem to humans is trees to houses.

A palm tree can live along the coast because it’s hardy and it can weather those hurricanes. But an oak tree or a sycamore tree - don’t see those along the coast because they can’t withstand a hurricane.

Palm trees have grown to become resistant. It’s the same with our building.

Think of like that little one-story beach bungalow as an oak tree or a sycamore tree. It can’t withstand the hurricanes.

So instead, let’s build resistance to hurricanes.

They’re never going to go away.

Let that palm tree be that big house on those 20-foot stilts. That way they have a better chance of surviving a storm.

But the reality is, even those palm trees and homes high up on stilts are getting battered by stronger storms, much more frequently.

“We had Donna in 60. We 44 years later had Charlie. Eleven years later we had Irma, five years later we had Ian,” Everham said. “So that that seems like a trend.”

First Responders On The Move More

The trend of more hurricanes more frequently has first responders along the Gulf Coast and across the country busier and busier.

For the men and women that make up Texas A&M Task Force 1 Urban Search and Rescue, that means they’re out the door more than they’re at home.

“Texas A&M Task Force one is by far the busiest team in the country,” said Director of Task Force 1 Jeff Saunders.

He’s at the helm of the $7 million dollar cache of equipment.

Saunders has responded to every major hurricane in the last 20 years, including both Ian and Harvey.

Gage Goulding: “Is there an easier type of hurricane to respond to?”

Jeff Saunders: “There’s an easier type of one that goes into non-populated areas.

Whether it’s historic rains from Harvey or inundating storm surge from Ian, his team is not only trained but ready to respond to each storm.

“It’s still going to involve the same amount of search and rescue from our standpoint, because what we do is wide area search,” he said. “Wide area search is a process where we do not really rely on 911. We literally are going door to door and determining if anybody is, a survivor in any one of the houses that’s affected by the storm. We try to start at the worst spot that we can find, and we work out to the unaffected areas in that way. We’re trying to do the most good for the most people in the least amount of time. We’re trying to get our people in to, to rescue those that are the most affected and need help the worst.”

Lessons From Local Law Enforcement

The same goes for local law enforcement, which not only endures the hurricane, but also has to turn around and respond to the storm as soon as it’s safe to do so.

“There’s people out here waving for help, trying to get out,” said a helicopter pilot with the Lee County Sheriff’s Office. “And there were things still, like actively burning down.”

The pilots that flew KPRC2′s Gage Goulding over the Fort Myers and the barrier islands of Fort Myers Beach, Sanibel and Capitva were the first emergency responders in the air after Hurricane Ian passed over the area on September 28, 2022.

This morning Sheriff Carmine Marceno took a tour of Lee County to begin assessing damage caused by Hurricane Ian.

— Carmine Marceno - Florida’s Law and Order Sheriff (@SheriffLeeFL) September 29, 2022

We are devastated. Our hearts go out to every resident who is impacted. The Lee County Sheriffs Office is mobile and will stop at nothing to help our residents. pic.twitter.com/S4OsB8ajRv

I remember flying in the helicopter and people in high rise buildings, you know, 4 or 5, eight floors up, waving white sheets because they were stranded,” said Lee County Sheriff Carmine Marceno. “You feel helpless. I can see them. I can see they’re waving a white sheet. I just can’t get to them physically.”

As the head of the county’s leading law enforcement agency, Sheriff Marceno reflects back on the lessons he and his team learned through Hurricane Ian and what other hurircane-prone law enforcement agencies could take away from their experience.

“Make sure that you do everything you can utilizing in today’s social media. Every type of communication tool that you have and be consistent,” the sheriff said. “Get out there, like I did during the storm. Every single day at noon, I delivered updates to our citizens because a lot of times people lose communication and they don’t get to see everything.”

One of his big lessons was communication. The other is cracking down on crime from the get-go.

Gage Goulding: “How did you approach looting during and post-Ian?”

Sheriff Carmine Marceno: “The figurehead of the agency, the chief, the sheriff, whoever it may be, needs to come out very, very public immediately and setting the tone and saying, ‘Not in my county, not in my state.’ These people, unfortunately, have just been hit by a hurricane. And there’s [a] tremendous loss of property and even possibly life. We’re not going to be allowing anyone to victimize them again. You come and you try to hurt one of our residents or steal. You’re going to jail.”

Sheriff’s deputies told me Thursday afternoon these people were arrested for looting on Fort Myers Beach. pic.twitter.com/j8JKRremlP

— Gage Goulding - KPRC 2 (@GageGoulding) September 30, 2022

It’s not just crime.

First responders had to evacuate themselves as Ian bore down on Southwest Florida. This means they had to leave people behind who refused to evacuate their homes. Many did not make it.

“Storm surge is very real, and it killed a lot of people,” a chopper pilot told KPRC2′s Gage Goulding. “So, absolutely, if you’re told to evacuate, evacuate.”

Have A Plan To Come Back

We’ve all heard the importance of having a plan to get out of harm’s way if a hurricane heads in our direction.

But how about a good plan to get back?

On the island of Fort Myers Beach where roughly one-third of the island’s structures were totally destroyed and not a single car survived Ian’s storm surge, local leaders openly admit they dropped the ball when it came to a good plan to safely allow property owners back on the island in the days and weeks after Hurricane Ian.

That challenge of reentry is something that I would really caution your municipal, your local leaders, to make sure you have a really good plan not only to get out away from the storm, but to be able to come back to your community after the storm,” said Fort Myers Beach Vice Mayor Jim Atterholt. “Because if you can’t get back quickly, that’s when the additional damage from rain and mold and mildew, that’s when that all sets in and the quicker you can get your people back. We didn’t do a very good job of that and we didn’t have a very good plan. And that’s not going to happen again if I can have anything to say about it.”

However, their biggest issue is one that is out of Vice Mayor Atterholt’s hands. It’s one that Houstonians are already dealing with at home. And it’s a blaring alarm for any community that could be caught in the eye of a hurricane.

“Our primary obstacle to recovery has been the insurance companies,” Atterholt said. “I know that’s talked about a lot, and it’s easy to bash the insurance companies, but they clearly have failed Southwest Florida. I think for your folks and your viewers in Texas, they need to be prepared for the insurance industry to be nonresponsive.”

The slow or never arriving insurance checks have held some residents and businesses from building back.

It’s why, nearly two years later, there are still properties that look like they haven’t been touched since the day Ian made landfall.

It’s A Lesson We Can All Learn

With every hurricane comes a new set of lessons we all can learn from.

From Florida to Texas, each time a community is knocked down, it can help anothe rbuild back quicker in stronger.

In Southwest Florida, they’re no quite there yet, but they are close.

“I call it a functional Paradise,” Atterholt said while walking the beach. “People are able to live their lives here and function and enjoy the beauty of this island and the beaches and the weather and they’re putting their lives back together.”

It’s important for everyone to look at what others have learned from their hardships to better prepare for a storm and how to overcome the challenges.